Page Summary

-

The C++ Language Tutorial covers basic material and introduces advanced topics like dynamic memory, objects, classes, inheritance, polymorphism, templates, exceptions, and namespaces.

-

Object-Oriented Design tutorial provides a methodology that will be applied in the module's project.

-

Learn by Example #3 focuses on practicing with pointers, object-oriented design, multi-dimensional arrays, and classes/objects through provided examples.

-

Unit testing is a critical part of software engineering for checking functionality of small code modules in isolation.

-

Google uses Information Retrieval techniques, like inverted indexes and Boolean retrieval models, to process and rank documents for search.

C++ Language Tutorial

The early sections of this tutorial cover the basic material already presented in the last two modules, and provide more information on advanced concepts. Our focus in this module is on dynamic memory, and more details on objects and classes. Some advanced topics are also introduced, like inheritance, polymorphism, templates, exceptions and namespaces. We will study these later in the Advanced C++ course.

Object-Oriented Design

This is an excellent tutorial on object-oriented design. We will apply the methodology presented here in this module's project.

Learn by Example #3

Our focus in this module is on obtaining more practice with pointers, object-oriented design, multi-dimensional arrays, and classes/objects. Work through the following examples. We can't emphasize enough that the key to becoming a good programmer is practice, practice, practice!Exercise #1: More Practice with Pointers

If you need additional practice with pointers, read through this resource which covers all aspects of pointers and provides many program examples.

What's the output of the following program? Please do not run the program, but draw the memory picture to determine the output.

void Unknown(int *p, int num);

void HardToFollow(int *p, int q, int *num);

void Unknown(int *p, int num) {

int *q;

q = #

*p = *q + 2;

num = 7;

}

void HardToFollow(int *p, int q, int *num) {

*p = q + *num;

*num = q;

num = p;

p = &q;

Unknown(num, *p);

}

main() {

int *q;

int trouble[3];

trouble[0] = 1;

q = &trouble[1];

*q = 2;

trouble[2] = 3;

HardToFollow(q, trouble[0], &trouble[2]);

Unknown(&trouble[0], *q);

cout << *q << " " << trouble[0] << " " << trouble[2];

}Once you have determined the output by hand, run the program to see if you are correct.

Exercise #2: More Practice with Classes and Objects

If you need additional practice with classes and objects, here is a resource that goes through the implementation of two small classes. Take some time to do the exercises.

Exercise #3: Multi-Dimensional Arrays

Consider the following program:

const int kStudents = 25;

const int kProblemSets = 10;

// This function returns the highest grade in the Problem Set array.

int get_high_grade(int *a, int cols, int row, int col) {

int i, j;

int highgrade = *a;

for (i = 0; i < row; i++)

for (j = 0; j < col; j++)

if (*(a + i * cols + j) > highgrade) // How does this line work?

highgrade = *(a + i*cols + j);

return highgrade;

}

int main() {

int grades[kStudents][kProblemSets] = {

{75, 70, 85, 72, 84},

{85, 92, 93, 96, 86},

{95, 90, 83, 76, 97},

{65, 62, 73, 84, 73}

};

int std_num = 4;

int ps_num = 5;

int highest;

highest = get_high_grade((int *)grades, kProblemSets, std_num, ps_num);

cout << "The highest problem set score in the class is " << highest << endl;

return 0;

}There is a line in this program marked "How does this line work?" - can you figure it out? Here is our explanation.

Write a program that initializes a 3-dim array and fills the 3rd dimension value with the sum of all three indexes. Here is our solution.

Exercise #4: An Extensive OO Design Example

Here is a detailed object-oriented design example, that goes through the entire process from start to finish. The final code is written in the Java programming language, but you'll be able to read through it given how far you have come.

Please take the time to work through this entire example. It's a great illustration of the process, and the design tools that support it.

Unit Testing

Introduction

Testing is a critical part of the software engineering process. A unit test is a particular kind of test, which checks the functionality of a single, small module of source code. Unit testing is always done by the engineer, and is usually done at the same time they are coding the module. The test drivers you used to test the Composer and Database classes are examples of unit tests.

Unit Tests have the following characteristics. They...

- test a component in isolation

- are deterministic

- usually map onto a single class

- avoid dependencies on external resources, e.g. databases, files, network

- execute quickly

- can be run in any order

There are automated frameworks and methodologies that provide support and consistency for unit testing in large software engineering organizations. There are some sophisticated open source unit testing frameworks, which we'll learn about later in this lesson.

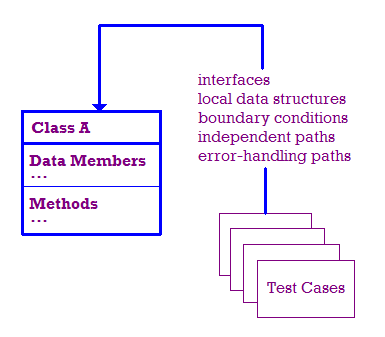

The tests that occur as a part of unit testing are illustrated below.

In an ideal world, we test for the following:

- The module interface is tested to make sure information flows in and out correctly.

- Local data structures are examined to make sure they store data properly.

- Boundary conditions are tested to make sure the module operates correctly at the boundaries that limit or restrict processing.

- We test independent paths through the module to make sure each path, and

thus each statement in the module, is executed at least once.

- Finally, we need to check that errors are handled properly.

Code Coverage

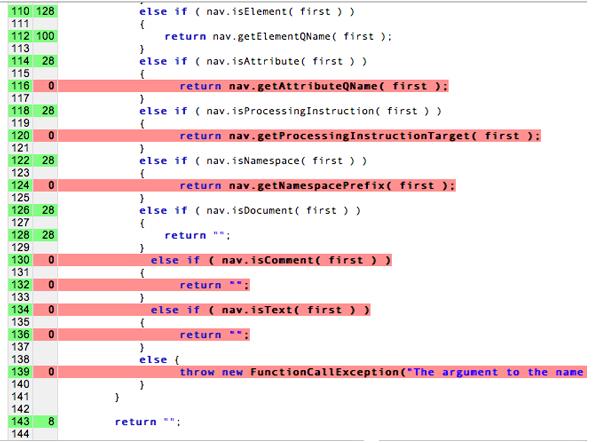

In reality, we cannot attain complete "code coverage" with our testing. Code coverage is an analysis method that determines which parts of a software system have been executed (covered) by the test case suite and which parts have not been executed. If we try and attain 100% coverage, we'll spend more time writing unit tests than writing the actual code! Consider coming up with unit tests for all independent paths of the following. This can quickly become an exponential problem.

In this diagram, the red lines are not tested, while the uncolored lines are tested.

Instead of attempting 100% coverage, we focus on tests that raise our confidence that the module is working properly. We test for things like:

- Null cases

- Range tests, e.g., positive/negative value tests

- Edge cases

- Failure cases

- Testing the paths most likely to execute most of the time

Unit Test Frameworks

Most unit test frameworks use assertions to test values during execution of a path. Assertions are statements that check whether a condition is true. The result of an assertion can be success, nonfatal failure , or fatal failure. After an assertion is performed, the program continues normally if the result is either success or nonfatal failure. If a fatal failure occurs, the current function is aborted.

Tests consist of code that sets up state or manipulates your module, coupled with a number of assertions which verify expected results. If all assertions in a test are successful, i.e., return true, then the test succeeds; otherwise it fails.

A test case contains one or many tests. We group tests into test cases that reflect the structure of the tested code. In this course, we are going to use CPPUnit as our unit test framework. With this framework, we can write unit tests in C++ and run them automatically, giving a report about the success or failure of tests.

CPPUnit Installation

Download the CPPUnit code from SourceForge. Find an appropriate directory and place the tar.gz file there. Then, enter the following commands (in Linux, Unix), substituting the appropriate cppunit file name:

gunzip filename.tar.gz tar -xvf filename.tar

If you are working in Windows, you may need to find a utility to extract tar.gz files. The next step is to compile the libraries. Change to the cppunit directory. There is an INSTALL file there which provides specific instructions. Usually, you need to run:

./configure make install

If you encounter issues, refer to the INSTALL file. The libraries are usually found in the cppunit/src/cppunit directory. To check that the compile worked, go into the cppunit/examples/simple directory and type "make". If everything compiles okay, then you are all set.

There is an excellent tutorial available here. Please go through this tutorial and create the complex number class, and its associated unit tests. There are several additional examples in the cppunit/examples directory.

Why Do I Have to Do This???

Unit testing is critically important in industry for several reasons. You're already familiar with one reason: We need some way of checking our work while developing code. Even when we're developing a very small program, we instinctively write some sort of checker or driver to make sure that our program does what's expected.

From long experience, engineers know that the chances that a program will work on the first try are very small. Unit tests build on this idea by making testing programs self-checking and repeatable. The assertions take the place of manually inspecting output. And, because it's easy to interpret the results (the test either passes or fails), the tests can be run over and over again, providing a safety net that makes your code more resilient to change.

Let's put this in concrete terms: When you first submit your finished code into CVS, it works perfectly. And it continues to work perfectly for a while. Then one day, someone else changes your code. Sooner or later that someone will break your code. Do you suppose they'll notice on their own? Not likely. But when you write unit tests, there are systems that can run them, automatically, every day. These are called continuous integration systems. So when that engineer X breaks your code, the system will send nasty emails to them until they fix it. Even if engineer X is YOU!

In addition to helping you develop software, and then keeping that software safe in the face of change, unit testing:

- Creates an executable specification, and documentation that stays in sync with the code. In other words, you can read a unit test to learn about what behavior the module supports.

- Helps you separate requirements from implementation. Because you're asserting externally visible behavior, you get the opportunity to think about it explicitly instead of mixing in ideas about how to implement the behavior.

- Supports experimentation. If you've got a safety net to alert you to when you've broken the behavior of a module, you're more likely to try things out and reconfigure your designs.

- Improves your designs. Writing thorough unit tests often requires you to make your code more testable. Testable code is often more modular than un-testable code.

- Keeps quality high. A small bug in a critical system can cause a company to lose millions of dollars, or even worse, a user's happiness or trust. The safety net that unit tests provide lessens this possibility. By catching bugs early, they also enable QA teams to spend time on more sophisticated and difficult failure scenarios, rather than reporting obvious failures.

Take some time to write unit tests using CPPUnit for the Composer database application. Refer to the cppunit/examples/ directory for help.

How Google Works

IntroductionImagine a monk in the Middle Ages looking at the thousands of manuscripts in the archives of his monastery. “Where is that one by Aristotle…”

Fortunately for him, the manuscripts are organized by content and inscribed with special symbols to facilitate retrieval of the information contained in each. Without such organization, it would be very difficult to find the relevant manuscript.

The activity of storing and retrieving written information from large collections is called Information Retrieval (IR). This activity has become increasingly important over the centuries, especially with inventions like paper and the printing press. It used to be something in which only a few people were occupied. Now, however, hundreds of millions of people engage in information retrieval every day when they use a search engine or search their desktop.

Getting Started with Information Retrieval

Dr. Seuss wrote 46 children’s books over the course of 30 years. His books told of cats, cows and elephants, of who’s, grinches and the lorax. Do you remember which creatures were in which story? Unless you are a parent, only children can tell you which set of Dr. Seuss stories have the creatures:

(COW and BEE) or CROWS

We will apply some classic information retrieval models to help us solve this problem.

An obvious approach is brute force: Obtain all 46 Dr. Seuss stories, and start reading. For each book, note which one(s) contain the words COW and BEE, and at the same time, look for books that contain the word CROWS. Computers are much faster at this than we are. If we have all the text from the Dr. Seuss books in digital form, say as text files, we can just grep through the files. For a small collection like Dr. Seuss’ books, this technique works fine.

There are many situations, however, where we need more. For example, the collection of all data currently online is way too big for grep to handle. We also don’t just want the documents that match our condition, we have become accustomed to having them ranked according to their relevance.

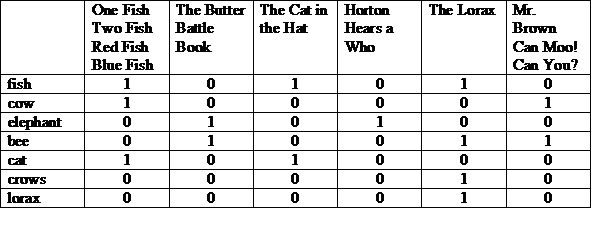

Another approach besides grep, is to create an index of the documents in a collection in advance of doing the search. An index in IR is similar to an index at the back of a textbook. We make a list of all the words (or terms) in each Dr. Seuss story, leaving out words like “the”, “and”, and other connectives, prepositions, etc. (these are called stop-words). We then represent this information in a way that facilitates finding the terms and identifying the stories they are in.

One possible representation is a matrix with the stories across the top, and the terms listed on each row. A “1” in a column indicates that the term appears in the story for that column.

We can view each row or column as a bit vector. A row’s bit vector indicates in which stories the term appears. A column’s bit vector indicates what terms appear in the story.

Returning to our original problem:

(COW and BEE) or CROWS

We take the bit vectors for these terms and first do a bit-wise AND, then do a bit-wise OR on the result.

(100001 and 010011) or 000010 = 000011

The answer: “Mr. Brown Can Moo! Can You?” and “The Lorax”. This is an illustration of the Boolean Retrieval model, which is an “exact match” model.

Suppose we were to expand the matrix to include all Dr. Seuss stories and all relevant terms in the stories. The matrix would grow considerably, and an important observation is most of the entries would be 0. A matrix is probably not the best representation for the index. We need to find a way to store just the 1’s.

Some Enhancements

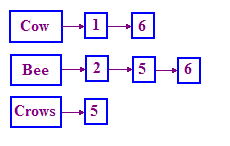

The structure used in IR to solve this problem is called an inverted index. We keep a dictionary of terms, and then for each term, we have a list that records the documents in which the term occurs. This list is called a postings list. A singly linked list works well to represent this structure as shown below.

If you are not familiar with linked lists, just do a Google search on "linked

list in C++", and you'll find many resources describing how to create one,

and how it's used. We will cover this in more detail in a later module.

Notice that we use Document IDs (DocIDs) instead of the name of the story. We also sort these DocIDs as it facilitates processing queries.

How do we process a query? For the original problem, we first find the COW postings list, then the BEE postings list. We then “merge” them together:

- Maintain markers into both lists and walk through the two postings lists simultaneously.

- At each step, compare the DocID pointed to by both pointers.

- If they are the same, put that DocID in a result list, else advance the pointer pointing to the smaller docID.

Here is how we can build an inverted index:

- Assign a DocID to each document of interest.

- For each document, identify its relevant terms (tokenize).

- For each term, create a record consisting of the term, the DocID where it is found, and a frequency in that document. Note that there can be multiple records for a particular term if it appears in more than one document.

- Sort the records by term.

- Create the dictionary and postings list by processing single records for a term, and also combining the multiple records for terms that appear in more than one document. Create a linked list of the DocIDs (in sorted order). Each term also has a frequency which is the sum of the frequencies across all records for a term.

The Project

Find several lengthy plaintext documents with which you can experiment. The project is to create an inverted index from the documents, using the algorithms described above. You will also need to create an interface for input of queries and an engine for processing them. You can find a project partner on the forum.

Here is a possible process for completing this project:

- The first thing to do is define a strategy for identifying terms in the documents. Make a list of all the stop-words you can think of, and write a function that reads through the words in the files, saves the terms, and eliminates the stop-words. You may have to add more stop-words to your list as you review the list of terms from an iteration.

- Write CPPUnit test cases to test your function, and a makefile to bring everything together for your build. Check your files into CVS, particularly if you are working with partners. You may want to research how to open up your CVS instance to remote engineers.

- Add processing to include location data, that is, which file and where in the file is a term located? You may want to figure out a calculation to define page number or paragraph number.

- Write CPPUnit test cases to test this additional functionality.

- Create an inverted index and store the location data in each term's record.

- Write more test cases.

- Design an interface to allow a user to enter a query.

- Using the search algorithm described above, process the inverted index and return the location data to the user.

- Be sure to include test cases for this final part as well.

As we have done on all projects, use the forum and chat to find project partners and to share ideas.

An Extra Feature

A common processing step in many IR systems is called stemming. The main idea behind stemming is that users searching for information on “retrieval” will also be interested in documents that have information containing “retrieve”, “retrieved”, “retrieving”, and so on. Systems can be susceptible to errors due to poor stemming, so this is a little tricky. For example, a user interested in “information retrieval” might get a document titled “Information on Golden Retrievers” due to stemming. A useful algorithm for stemming is the Porter algorithm.