语音输入哈希表

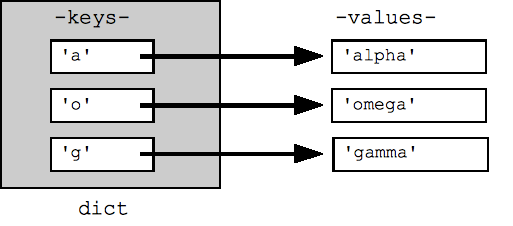

Python 高效的键/值哈希表结构称为“字典”。字典的内容可以写成用大括号 { } 括起来的一系列键值对,例如dict = {key1:value1, key2:value2, ... }。“空字典”只是一对空的大括号 {}。

在字典中查找或设置值时,可以使用方括号,例如dict['foo'] 会查找键“foo”下的值。字符串、数字和元组用作键,任何类型都可以是值。其他类型可能会或不能作为键正确运行(字符串和元组是不可变的,因此能够正常发挥作用)。如果查找字典中没有的值,则会抛出 KeyError - 使用“in”检查键是否在字典中,或使用 dict.get(key) 返回值,如果键不存在,则使用 None(或者 get(key, not-found) 指定在未找到的情况下要返回的值)。

## Can build up a dict by starting with the empty dict {} ## and storing key/value pairs into the dict like this: ## dict[key] = value-for-that-key dict = {} dict['a'] = 'alpha' dict['g'] = 'gamma' dict['o'] = 'omega' print(dict) ## {'a': 'alpha', 'o': 'omega', 'g': 'gamma'} print(dict['a']) ## Simple lookup, returns 'alpha' dict['a'] = 6 ## Put new key/value into dict 'a' in dict ## True ## print(dict['z']) ## Throws KeyError if 'z' in dict: print(dict['z']) ## Avoid KeyError print(dict.get('z')) ## None (instead of KeyError)

默认情况下,字典上的 for 循环会迭代其键。密钥以任意顺序显示。dict.keys() 和 dict.values() 方法会明确返回键或值的列表。此外,还有一种 items() 可返回 (key, value) 元组的列表,这是检查字典中所有键值对数据的最有效方式。所有这些列表都可以传递给 Sort() 函数。

## By default, iterating over a dict iterates over its keys. ## Note that the keys are in a random order. for key in dict: print(key) ## prints a g o ## Exactly the same as above for key in dict.keys(): print(key) ## Get the .keys() list: print(dict.keys()) ## dict_keys(['a', 'o', 'g']) ## Likewise, there's a .values() list of values print(dict.values()) ## dict_values(['alpha', 'omega', 'gamma']) ## Common case -- loop over the keys in sorted order, ## accessing each key/value for key in sorted(dict.keys()): print(key, dict[key]) ## .items() is the dict expressed as (key, value) tuples print(dict.items()) ## dict_items([('a', 'alpha'), ('o', 'omega'), ('g', 'gamma')]) ## This loop syntax accesses the whole dict by looping ## over the .items() tuple list, accessing one (key, value) ## pair on each iteration. for k, v in dict.items(): print(k, '>', v) ## a > alpha o > omega g > gamma

策略说明:从性能的角度来看,字典是最实用的工具之一,您应该将其用于轻松整理数据的地方。例如,您可以读取一个日志文件,其中每行都以 IP 地址开头,并使用 IP 地址作为键,使用 IP 地址作为值的行列表将数据存储在字典中。读完整个文件后,您可以查找任何 IP 地址,并立即看到其行列表。字典接受分散的数据,并将其转换为连贯的内容。

语音输入格式

% 运算符可以方便地按名称将字典中的值替换为字符串:

h = {} h['word'] = 'garfield' h['count'] = 42 s = 'I want %(count)d copies of %(word)s' % h # %d for int, %s for string # 'I want 42 copies of garfield' # You can also use str.format(). s = 'I want {count:d} copies of {word}'.format(h)

Del

“del”命令操作员执行删除操作。在最简单的情况下,它可以移除变量的定义,就好像该变量尚未定义一样。Del 也可用于列表元素或切片,以删除列表中的相应部分以及从字典中删除条目。

var = 6 del var # var no more! list = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] del list[0] ## Delete first element del list[-2:] ## Delete last two elements print(list) ## ['b'] dict = {'a':1, 'b':2, 'c':3} del dict['b'] ## Delete 'b' entry print(dict) ## {'a':1, 'c':3}

文件

open() 函数会打开并返回一个文件句柄,该句柄可用于以常规方式读取或写入文件。代码 f = open('name', 'r') 将文件打开到变量 f 中,为读取操作做好准备,并在完成后使用 f.close()。使用“w”代替“r”和“a”用于附加。标准的 for 循环适用于文本文件,用于遍历文件的行(仅适用于文本文件,不适用于二进制文件)。for 循环技术是一种查看文本文件中所有行的简单高效的方法:

# Echo the contents of a text file f = open('foo.txt', 'rt', encoding='utf-8') for line in f: ## iterates over the lines of the file print(line, end='') ## end='' so print does not add an end-of-line char ## since 'line' already includes the end-of-line. f.close()

一次阅读一行的优点在于,并非所有文件都需要同时在内存中放好;如果您希望查看 10 GB 文件中的每一行,而不使用 10 GB 内存,此功能就非常方便。f.readlines() 方法可将整个文件读取到内存中,并以文件行列表形式返回文件内容。f.read() 方法可将整个文件读取到单个字符串中,这是一次性处理文本的便捷方法,例如使用正则表达式(我们稍后将对此进行介绍)。

对于写入,f.write(string) 方法是将数据写入打开的输出文件的最简单方法。或者,您也可以使用“打印”选项输出为“print(string, file=f)”这样的打开文件。

文件 Unicode

如需读取和写入 Unicode 编码文件,请使用 `'t'` 模式并明确指定编码:

with open('foo.txt', 'rt', encoding='utf-8') as f: for line in f: # here line is a *unicode* string with open('write_test', encoding='utf-8', mode='wt') as f: f.write('\u20ACunicode\u20AC\n') # €unicode€ # AKA print('\u20ACunicode\u20AC', file=f) ## which auto-adds end='\n'

练习增量开发

要构建 Python 程序,不要一步到位,而应仅指定第一个里程碑,例如“第一步是提取字词列表。”编写代码以实现该里程碑,然后仅输出当时的数据结构,然后您可以执行 sys.exit(0),这样程序就不会直接运行到未完成的部分。里程碑代码正常运行后,您便可以为下一个里程碑编写代码。观察变量在一种状态下的输出,有助于思考需要如何转换这些变量,才能达到下一状态。使用此模式时,Python 非常快,允许您稍作更改并运行该程序以查看其工作方式。利用这种快速的周转时间,在几步之内构建您的计划。

练习:wordcount.py

结合所有基本 Python 资料(字符串、列表、字典、元组、文件),请尝试基本练习中的 wordcount.py 总结练习。