Dict Hash Table

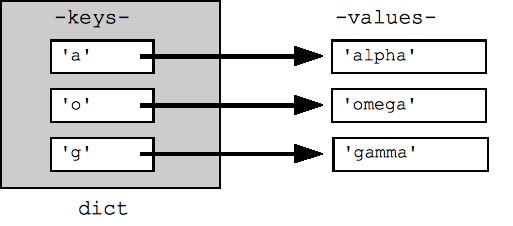

ساختار جدول هش کلید/مقدار کارآمد پایتون "دیکت" نامیده می شود. محتویات یک dict را می توان به صورت مجموعه ای از جفت های کلید:مقدار در داخل پرانتزهای { } نوشت، به عنوان مثال dict = {key1:value1، key2:value2، ... }. "Empty dict" فقط یک جفت پرانتز مجعد خالی {} است.

جستجو کردن یا تنظیم یک مقدار در یک dict از کروشه استفاده می کند، به عنوان مثال dict['foo'] مقدار را در زیر کلید 'foo' جستجو می کند. رشته ها، اعداد و تاپل ها به عنوان کلید کار می کنند و هر نوع می تواند یک مقدار باشد. انواع دیگر ممکن است به عنوان کلید به درستی کار کنند یا ممکن است به درستی کار نکنند (رشته ها و تاپل ها تمیز کار می کنند زیرا تغییرناپذیر هستند). جستجوی مقداری که در دیکته نیست، یک خطای کلیدی ایجاد میکند - از "in" برای بررسی اینکه آیا کلید در دیکته است یا نه از dict.get(key) استفاده کنید که مقدار را برمیگرداند یا اگر کلید وجود نداشته باشد، از None استفاده کنید. یا get(key, not-found) به شما این امکان را می دهد که مشخص کنید چه مقداری را در حالت پیدا نشده برگردانید).

## Can build up a dict by starting with the empty dict {} ## and storing key/value pairs into the dict like this: ## dict[key] = value-for-that-key dict = {} dict['a'] = 'alpha' dict['g'] = 'gamma' dict['o'] = 'omega' print(dict) ## {'a': 'alpha', 'o': 'omega', 'g': 'gamma'} print(dict['a']) ## Simple lookup, returns 'alpha' dict['a'] = 6 ## Put new key/value into dict 'a' in dict ## True ## print(dict['z']) ## Throws KeyError if 'z' in dict: print(dict['z']) ## Avoid KeyError print(dict.get('z')) ## None (instead of KeyError)

یک حلقه for در فرهنگ لغت به طور پیش فرض روی کلیدهای آن تکرار می شود. کلیدها به ترتیب دلخواه ظاهر می شوند. متدهای dict.keys() و dict.values() لیستی از کلیدها یا مقادیر را به طور صریح برمی گرداند. همچنین یک آیتم() وجود دارد که لیستی از تاپل های (key, value) را برمی گرداند که کارآمدترین راه برای بررسی تمام داده های مقدار کلید در فرهنگ لغت است. همه این لیست ها را می توان به تابع sorted() منتقل کرد.

## By default, iterating over a dict iterates over its keys. ## Note that the keys are in a random order. for key in dict: print(key) ## prints a g o ## Exactly the same as above for key in dict.keys(): print(key) ## Get the .keys() list: print(dict.keys()) ## dict_keys(['a', 'o', 'g']) ## Likewise, there's a .values() list of values print(dict.values()) ## dict_values(['alpha', 'omega', 'gamma']) ## Common case -- loop over the keys in sorted order, ## accessing each key/value for key in sorted(dict.keys()): print(key, dict[key]) ## .items() is the dict expressed as (key, value) tuples print(dict.items()) ## dict_items([('a', 'alpha'), ('o', 'omega'), ('g', 'gamma')]) ## This loop syntax accesses the whole dict by looping ## over the .items() tuple list, accessing one (key, value) ## pair on each iteration. for k, v in dict.items(): print(k, '>', v) ## a > alpha o > omega g > gamma

نکته استراتژی: از نقطه نظر عملکرد، فرهنگ لغت یکی از بهترین ابزارهای شماست و باید از آن در جایی که می توانید به عنوان راهی آسان برای سازماندهی داده ها استفاده کنید. برای مثال، ممکن است یک فایل گزارش را بخوانید که در آن هر خط با یک آدرس IP شروع میشود و دادهها را با استفاده از آدرس IP بهعنوان کلید و فهرست خطوطی که بهعنوان مقدار نشان داده میشود، در یک دیکت ذخیره کنید. پس از خواندن کل فایل، می توانید هر آدرس IP را جستجو کنید و فوراً لیست خطوط آن را مشاهده کنید. فرهنگ لغت داده های پراکنده را می گیرد و آن را به چیزی منسجم تبدیل می کند.

فرمت دیکت

عملگر % به راحتی کار می کند تا مقادیر را از یک dict به یک رشته با نام جایگزین کند:

h = {} h['word'] = 'garfield' h['count'] = 42 s = 'I want %(count)d copies of %(word)s' % h # %d for int, %s for string # 'I want 42 copies of garfield' # You can also use str.format(). s = 'I want {count:d} copies of {word}'.format(h)

دل

عملگر "del" حذف ها را انجام می دهد. در ساده ترین حالت، می تواند تعریف یک متغیر را حذف کند، گویی آن متغیر تعریف نشده است. همچنین میتوان از Del در عناصر یا برشهای فهرست برای حذف آن قسمت از فهرست و حذف مدخلهای یک فرهنگ لغت استفاده کرد.

var = 6 del var # var no more! list = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] del list[0] ## Delete first element del list[-2:] ## Delete last two elements print(list) ## ['b'] dict = {'a':1, 'b':2, 'c':3} del dict['b'] ## Delete 'b' entry print(dict) ## {'a':1, 'c':3}

فایل ها

تابع open() باز می شود و دسته فایلی را برمی گرداند که می توان از آن برای خواندن یا نوشتن یک فایل به روش معمول استفاده کرد. کد f = open('name', 'r') فایل را در متغیر f باز می کند که برای خواندن عملیات آماده است و پس از اتمام از f.close() استفاده کنید. به جای r، برای نوشتن از «w» و برای ضمیمه از «a» استفاده کنید. حلقه استاندارد برای فایلهای متنی کار میکند و از طریق خطوط فایل تکرار میشود (این فقط برای فایلهای متنی کار میکند، نه فایلهای باینری). تکنیک for-loop یک روش ساده و کارآمد برای مشاهده تمام خطوط در یک فایل متنی است:

# Echo the contents of a text file f = open('foo.txt', 'rt', encoding='utf-8') for line in f: ## iterates over the lines of the file print(line, end='') ## end='' so print does not add an end-of-line char ## since 'line' already includes the end-of-line. f.close()

خواندن یک خط در یک زمان دارای کیفیت خوبی است که لازم نیست همه فایل ها در یک زمان در حافظه قرار گیرند - اگر بخواهید بدون استفاده از 10 گیگابایت حافظه به هر خط در یک فایل 10 گیگابایتی نگاه کنید مفید است. متد f.readlines() کل فایل را در حافظه می خواند و محتویات آن را به عنوان لیستی از خطوط آن برمی گرداند. متد f.read() کل فایل را در یک رشته می خواند، که می تواند روشی مفید برای مقابله با متن به یکباره باشد، مانند عبارات منظم که بعداً خواهیم دید.

برای نوشتن، روش f.write(string) ساده ترین راه برای نوشتن داده در یک فایل خروجی باز است. یا می توانید از "print" با یک فایل باز مانند "print(string, file=f)" استفاده کنید.

فایل های یونیکد

برای خواندن و نوشتن فایلهای رمزگذاریشده یونیکد از حالت «t» استفاده کنید و به صراحت یک رمزگذاری را مشخص کنید:

with open('foo.txt', 'rt', encoding='utf-8') as f: for line in f: # here line is a *unicode* string with open('write_test', encoding='utf-8', mode='wt') as f: f.write('\u20ACunicode\u20AC\n') # €unicode€ # AKA print('\u20ACunicode\u20AC', file=f) ## which auto-adds end='\n'

توسعه تدریجی تمرین کنید

در ساخت یک برنامه پایتون، همه چیز را در یک مرحله ننویسید. به جای آن فقط یک نقطه عطف اول را مشخص کنید، به عنوان مثال "خوب اولین قدم استخراج لیست کلمات است." کد را بنویسید تا به آن نقطه عطف برسید، و فقط ساختارهای داده خود را در آن نقطه چاپ کنید، و سپس می توانید یک sys.exit(0) انجام دهید تا برنامه در قسمت های انجام نشده اش اجرا نشود. هنگامی که کد نقطه عطف کار می کند، می توانید روی کد برای نقطه عطف بعدی کار کنید. اینکه بتوانید به پرینت متغیرهای خود در یک حالت نگاه کنید، می تواند به شما کمک کند تا در مورد چگونگی تغییر آن متغیرها برای رسیدن به حالت بعدی فکر کنید. پایتون با این الگو بسیار سریع عمل می کند و به شما امکان می دهد کمی تغییر دهید و برنامه را اجرا کنید تا ببینید چگونه کار می کند. از این چرخش سریع برای ساختن برنامه خود در مراحل کوچک استفاده کنید.

تمرین: wordcount.py

با ترکیب تمام مواد اولیه پایتون - رشتهها، فهرستها، دستورات، تاپلها، فایلها - تمرین خلاصه wordcount.py را در تمرینهای پایه امتحان کنید.