جدول تجزئة الإملاء

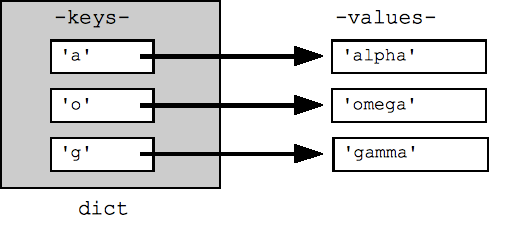

يُطلق على بنية جدول تجزئة المفتاح/القيمة الفعّالة في بايثون اسم "dict". يمكن كتابة محتوى الأمر كسلسلة من أزواج المفتاح/القيمة داخل الأقواس { }، على سبيل المثال dict = {key1:value1, key2:value2, ... }. "الإملاء الفارغ" هو مجرد زوج فارغ من الأقواس المعقوفة {}.

يمكن استخدام أقواس مربّعة للبحث عن قيمة أو ضبطها في القاموس، على سبيل المثال. يبحث الأمر dict['foo'] عن القيمة ضمن المفتاح 'foo'. تعمل السلاسل والأرقام والصفوف كمفاتيح، ويمكن أن يكون أي نوع قيمة. قد تعمل الأنواع الأخرى أو لا تعمل بشكل صحيح كمفاتيح (تعمل السلاسل والصفوف بسلاسة لأنها غير قابلة للتغيير). يؤدي البحث عن قيمة ليست في القاموس إلى عرض خطأ KeyError -- استخدام "in" للتحقق مما إذا كان المفتاح في القاموس، أو استخدم dict.get(key) التي تعرض القيمة أو None إذا كان المفتاح غير موجود (أو يسمح لك get(key, not-found) بتحديد القيمة التي تريد عرضها في حالة عدم العثور عليها).

## Can build up a dict by starting with the empty dict {} ## and storing key/value pairs into the dict like this: ## dict[key] = value-for-that-key dict = {} dict['a'] = 'alpha' dict['g'] = 'gamma' dict['o'] = 'omega' print(dict) ## {'a': 'alpha', 'o': 'omega', 'g': 'gamma'} print(dict['a']) ## Simple lookup, returns 'alpha' dict['a'] = 6 ## Put new key/value into dict 'a' in dict ## True ## print(dict['z']) ## Throws KeyError if 'z' in dict: print(dict['z']) ## Avoid KeyError print(dict.get('z')) ## None (instead of KeyError)

يتكرر التكرار الحلقي for في القاموس على مفاتيحه افتراضيًا. ستظهر المفاتيح بترتيب عشوائي. تُرجع الطريقتان dict.keys() وdict.values() قوائم بالمفاتيح أو القيم بشكل صريح. هناك أيضًا items() التي تُرجع قائمة بالصفوف (المفتاح، القيمة)، وهي الطريقة الأكثر فاعلية لفحص جميع بيانات القيمة الرئيسية في القاموس. يمكن تمرير جميع هذه القوائم إلى الدالة sorted().

## By default, iterating over a dict iterates over its keys. ## Note that the keys are in a random order. for key in dict: print(key) ## prints a g o ## Exactly the same as above for key in dict.keys(): print(key) ## Get the .keys() list: print(dict.keys()) ## dict_keys(['a', 'o', 'g']) ## Likewise, there's a .values() list of values print(dict.values()) ## dict_values(['alpha', 'omega', 'gamma']) ## Common case -- loop over the keys in sorted order, ## accessing each key/value for key in sorted(dict.keys()): print(key, dict[key]) ## .items() is the dict expressed as (key, value) tuples print(dict.items()) ## dict_items([('a', 'alpha'), ('o', 'omega'), ('g', 'gamma')]) ## This loop syntax accesses the whole dict by looping ## over the .items() tuple list, accessing one (key, value) ## pair on each iteration. for k, v in dict.items(): print(k, '>', v) ## a > alpha o > omega g > gamma

ملاحظة حول الإستراتيجية: من منظور الأداء، يُعد القاموس أحد أعظم أدواتك، ويجب استخدامه حيث يمكنك استخدامه كطريقة سهلة لتنظيم البيانات. على سبيل المثال، قد تقرأ ملف سجلّ يبدأ فيه كل سطر بعنوان IP، وتخزن البيانات في إملاء باستخدام عنوان IP كمفتاح، وقائمة الأسطر التي يظهر فيها كقيمة. بمجرد قراءة الملف بأكمله، يمكنك البحث عن أي عنوان IP وعرض قائمة السطور الخاصة به على الفور. يأخذ القاموس البيانات المبعثرة ويجعلها شيئًا مترابطًا.

تنسيق الإملاء

يعمل عامل التشغيل % بشكل ملائم لاستبدال القيم من الإملاء في سلسلة بالاسم:

h = {} h['word'] = 'garfield' h['count'] = 42 s = 'I want %(count)d copies of %(word)s' % h # %d for int, %s for string # 'I want 42 copies of garfield' # You can also use str.format(). s = 'I want {count:d} copies of {word}'.format(h)

حذف

إن "ديل" عمليات الحذف. في أبسط الحالات، يمكنه إزالة تعريف متغير، كما لو لم يتم تحديد ذلك المتغير. يمكن أيضًا استخدام ديل في عناصر القائمة أو الشرائح لحذف هذا الجزء من القائمة وحذف الإدخالات من القاموس.

var = 6 del var # var no more! list = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'] del list[0] ## Delete first element del list[-2:] ## Delete last two elements print(list) ## ['b'] dict = {'a':1, 'b':2, 'c':3} del dict['b'] ## Delete 'b' entry print(dict) ## {'a':1, 'c':3}

الملفات

تفتح الدالة open() وترجع مؤشر ملف يمكن استخدامه لقراءة ملف أو كتابته بالطريقة المعتادة. التعليمة البرمجية f = open('name', 'r') تفتح الملف في المتغير f، جاهزًا لعمليات القراءة، ويستخدم f.Close() عند الانتهاء. بدلاً من "r"، استخدِم "w" للكتابة، و"a" من أجل append. تعمل الحلقة القياسية للملفات النصية، وتتكرر عبر أسطر الملف (هذا يعمل فقط مع الملفات النصية، وليس الملفات الثنائية). أسلوب التكرار الحلقي هو طريقة بسيطة وفعالة للنظر في جميع الأسطر في ملف نصي:

# Echo the contents of a text file f = open('foo.txt', 'rt', encoding='utf-8') for line in f: ## iterates over the lines of the file print(line, end='') ## end='' so print does not add an end-of-line char ## since 'line' already includes the end-of-line. f.close()

تتمتع قراءة سطر واحد في كل مرة بجودة جيدة لا يحتاج كل الملف إلى استخدامها في الذاكرة في وقت واحد -- وهو أمر مفيد إذا كنت تريد الاطلاع على كل سطر في ملف 10 غيغابايت دون استخدام 10 غيغابايت من الذاكرة. تقرأ الطريقة f.readlines() الملف بأكمله في الذاكرة وتعرض محتوياته كقائمة سطوره. تقرأ الطريقة f.read() الملف بأكمله في سلسلة واحدة، والتي يمكن أن تكون طريقة سهلة للتعامل مع النص مرة واحدة، كما هو الحال مع التعبيرات العادية التي ستراها لاحقًا.

للكتابة، تعد طريقة f.write(string) أسهل طريقة لكتابة البيانات في ملف إخراج مفتوح. أو يمكنك استخدام "الطباعة" بملف مفتوح مثل "print(string, file=f)".

يونيكود للملفات

لقراءة وكتابة الملفات بترميز يونيكود، يجب استخدام وضع "'t" وتحديد الترميز بشكل صريح:

with open('foo.txt', 'rt', encoding='utf-8') as f: for line in f: # here line is a *unicode* string with open('write_test', encoding='utf-8', mode='wt') as f: f.write('\u20ACunicode\u20AC\n') # €unicode€ # AKA print('\u20ACunicode\u20AC', file=f) ## which auto-adds end='\n'

التنمية التزايدية في التمارين

عند إنشاء برنامج بايثون، لا تكتب كل شيء في خطوة واحدة. بدلاً من ذلك، حدد المعلم الرئيسي الأول فقط، على سبيل المثال "حسنًا، الخطوة الأولى هي استخراج قائمة الكلمات". اكتب التعليمة البرمجية للوصول إلى هذا المعلم الرئيسي، واطبع فقط هياكل البيانات في هذه المرحلة، ثم يمكنك إجراء sys.exit(0) حتى لا يبدأ البرنامج في العمل إلى أجزائه غير المكتملة. بمجرد عمل رمز المعلم الرئيسي، يمكنك العمل على رمز المعلم الرئيسي التالي. يمكن أن تساعدك القدرة على إلقاء نظرة على النسخة المطبوعة من المتغيرات الخاصة بك في حالة واحدة في التفكير في كيفية تحويل هذه المتغيرات للوصول إلى الحالة التالية. تتميز بايثون بسرعة كبيرة باستخدام هذا النمط، فهي تتيح لك إجراء تغيير بسيط وتشغيل البرنامج للتعرف على طريقة عمله. استفد من هذا التحول السريع لبناء برنامجك بخطوات بسيطة.

تمرين: wordcount.py

عند الجمع بين جميع مواد بايثون الأساسية، مثل السلاسل، والقوائم، والإملاء، والصفوف، والملفات -- جرّب تمرين الملخص wordcount.py في التمارين الأساسية.